This 2014 paper on cost pass-through is a nice summary.

Our discussion of relevant theory is framed in terms of absolute pass-through: the degree to

which a given absolute change in cost causes an absolute change in price

The extent of industry-wide cost pass-through in a perfectly competitive market depends on

the elasticity of demand relative to supply. The more elastic is demand, and the less elastic

is supply, the smaller the extent of pass-through, all else being equal

With other market structures, economic theory indicates that:

– Pass-through depends on the curvature of demand. It is greater with convex inverse demand (the inverse demand curve becomes steeper as output decreases) and

smaller with concave inverse-demand (the inverse demand curve becomes flatter as

output decreases), all else being equal.

– Pass-through is smaller when marginal cost curves slope upwards (i.e. marginal cost

increases as output increases) and greater when marginal cost curves slope

downwards (i.e. marginal cost falls as output increases).

– Pass-through in excess of 100% is possible when inverse-demand is convex enough

and/or when there are strong increasing returns to scale such that marginal cost curves

slope sufficiently downwards. Industry-wide cost increases can result in increased

profits when demand is very convex.

Many theoretical models indicate that pass-through of industry-wide cost changes increases

with the intensity of competition1

, provided that inverse demand is not very convex,

The paper usefully illustrates some examples of industry curvature.

"Suppose that a monopolist faces an increase in its unit costs. The monopolist will consider its

scope to adjust its price upwards.

The monopolist will think: “how much output do I have to

sacrifice to pass on a certain amount of this change in my costs?” If the answer is “very little”,

passing on the cost shock will be more attractive; if the answer is “a lot”, passing on the cost

shock will be less attractive. The answer to the monopolist’s question is related to the curvature

of demand. Other things being equal, pass-through will be lower if inverse demand is concave

(because passing on the cost increase will cause a relatively large fall in output). On the other

hand, pass-through will be higher with convex demand (since passing on the cost increase has

a smaller impact on volumes)."

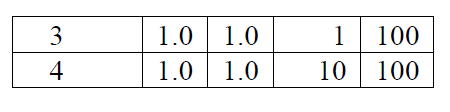

A useful formula in Genakos, 2019, summarises this.

where

- rho is the impact of an incrase in marginal cost on price

- theta is price marginal cost margin times product demand elasticity, an intensity of competition index (theta=0 competition, theta=1 monopoly)

- es the elasticity of supply

- ems is the curvature of demand (strictly the curvature of log demand).

- etheta how intensity varies with quantity

special cases